Eye floaters, flashes and spots

Eye floaters are those tiny spots, specks, flecks and "cobwebs" that drift aimlessly around in your field of vision. While annoying, ordinary eye floaters and spots are very common and usually aren't cause for alarm.

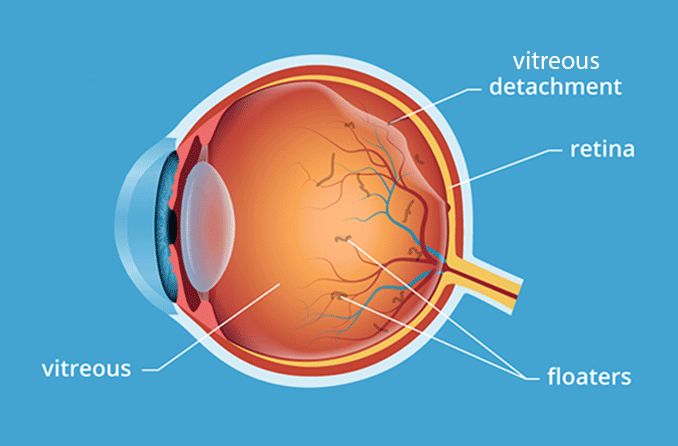

Floaters and spots typically appear when tiny pieces of the eye's gel-like vitreous break loose within the inner back portion of the eye.

At birth and throughout childhood, the vitreous has a gel-like consistency but as we age, the vitreous begins to dissolve and liquefy to create a watery centre.

Some undissolved gel particles occasionally will float around in the more liquid centre of the vitreous. These particles can take on many shapes and sizes to become what we refer to as "eye floaters."

You'll notice that these spots and floaters are particularly pronounced if you gaze at a clear or overcast sky or a computer screen with a white or light-coloured background. You won't actually be able to see tiny bits of debris floating loose within your eye. Instead, shadows from these floaters are cast on the retina as light passes through the eye, and those tiny shadows are what you see.

You'll also notice that these specks never seem to stay still when you try to focus on them. Floaters and spots move when your eye and the vitreous gel inside the eye moves, creating the impression that they are "drifting."

When are eye floaters and flashes a medical emergency?

Noticing a few floaters from time to time is not a cause for concern. However, if you see a shower of floaters and spots, especially if they are accompanied by flashes of light, you should seek medical attention immediately from your optometrist or ophthalmologist.

The sudden appearance of these symptoms could mean that the vitreous is pulling away from your retina — a condition called posterior vitreous detachment.

Alternatively it could mean that the retina itself is becoming dislodged from the back of the eye's inner lining, which contains blood, nutrients and oxygen vital to healthy function. As the vitreous gel tugs on the delicate retina, it might cause a small tear or hole in it. When the retina is torn, vitreous can enter the opening and push the retina farther away from the inner lining of the back of the eye — leading to a retinal detachment.

A detached retina is a medical emergency that requires immediate treatment to prevent permanent vision loss. Treatment consists of surgery to reattach the retina to the back surface of the eyeball, reconnecting it to its source of blood, oxygen and other nutrients.

Posterior vitreous detachments (PVDs) are far more common than retinal detachments and often are not an emergency even when floaters appear suddenly. Some vitreous detachments also can damage the retina by tugging on it, leading to a tear or detachment of a portion of the retina.

What causes eye floaters and spots?

As mentioned above, PVDs are common causes of vitreous floaters, and retinal tears and detachments also can contribute to floaters and spots.

What leads to vitreous detachments in the first place?

As the eye develops, the vitreous gel fills the inside of the back of the eye and presses against and attaches to the surface of the retina. Over time, the vitreous becomes more liquefied in the centre. This sometimes means that the central, more watery vitreous cannot support the weight of the heavier vitreous gel around the periphery. The peripheral vitreous gel then collapses into the central, liquefied vitreous, detaching from the retina.

It's estimated that more than half of all people will have a PVD by age 80. Thankfully, most of these vitreous detachments do not lead to a torn or detached retina.

Light flashes during this process mean that traction is being applied to your retina while the PVD takes place. Once the vitreous actually detaches from the retina this traction pressure is eased, and the light flashes should subside.

What causes eye flashes?

Ordinarily, light entering your eye stimulates the retina. This produces an electrical impulse, which the optic nerve transmits to the brain. The brain then interprets this impulse as light or some type of image.

If the retina is mechanically stimulated (physically touched or tugged), a similar electrical impulse is sent to the brain. This impulse is then interpreted as a flash or flicker of light called a photopsia.

When the retina is tugged, torn or detached from the back of the eye, a flash or flicker of light commonly is noticed. Depending on the extent of the traction, tear or detachment, these photopsias might be short-lived or continue indefinitely until the retina is repaired.

Photopsias also may occur after a blow to the head that is capable of shaking the vitreous gel inside the eye. When this occurs, the phenomenon sometimes is called "seeing stars." In some cases, photopsias are associated with migraine headaches and ocular migraines.

SEE RELATED: Optical and visual migraines explained

Other conditions associated with eye floaters and flashes

When a PVD is accompanied by bleeding inside the eye (vitreous hemorrhage), it means the traction that occurred may have torn a small blood vessel in the retina.

A vitreous hemorrhage increases the possibility of a retinal tear or detachment. Traction exerted on the retina during a PVD also can lead to development of conditions such as macular holes or puckers.

Vitreous detachments with accompanying eye floaters may also occur in circumstances such as:

Inflammation in the eye's interior

Higher levels of Short sightedness

YAG laser eye surgery

Diabetes (diabetic vitreopathy)

CMV retinitis

Inflammation associated with many conditions such as eye infections can cause the vitreous to liquefy, leading to a PVD.

When you are shor-tsighted, your eye's elongated shape also can increase the likelihood of a PVD and accompanying traction on the retina. Short-sighted people also are more likely to have PVDs at a younger age.

PVDs are very common following cataract surgery and a follow-up procedure called a YAG laser capsulotomy.

Months or even years after cataract surgery, it's not unusual for the thin membrane (or "capsule") that's left intact behind the interocular lens (IOL) to become cloudy, affecting vision. This delayed cataract surgery complication is called posterior capsular opacification (PCO).

In the capsulotomy procedure used to treat PCO, a special type of laser focuses energy onto the cloudy capsule, vaporising the central portion of it to create a clear path for light to reach the retina, which restores clear vision.

Manipulations of the eye during cataract surgery and YAG laser capsulotomy procedures cause traction that can lead to posterior vitreous detachments.

How to get rid of eye floaters

Most eye floaters and spots are harmless and merely annoying. Many will fade over time and become less bothersome. In most cases, no eye floaters treatment is required.

However, large persistent floaters can be very bothersome to some people, causing them to seek a way to get rid of eye floaters and spots drifting in their field of view.

However, the risks of a virectomy usually outweigh the benefits for eye floater treatment. These risks include surgically induced retinal detachment and serious eye infections. On rare occasions, vitrectomy surgery can cause new or even more floaters. For these reasons, most eye surgeons do not recommend vitrectomy to treat eye floaters and spots.

Laser treatment for floaters

A relatively new laser procedure called laser vitreolysis has been introduced that is a much safer alternative to vitrectomy for treating floaters.

In this in-office procedure, a laser beam is projected into the eye through the pupil and is focused on large floaters, which breaks them apart and/or frequently vaporises them so they disappear or become much less bothersome.

To determine if you can benefit from laser vitreolysis to get rid of floaters, your optometrist will consider several factors, including your age, how quickly your symptoms started, what your floaters look like and where they are located.

Many floaters in patients younger than age 45 may be located too close to the retina and can't be safely treated with laser vitreolysis. Patients with sizable eye floaters located farther away from the retina are better suited to the procedure.

An ophthalmologist who performs laser vitreolysis also will evaluate the shape and borders of your eye floaters. Those with "soft" borders often can be treated successfully. Likewise, sizable floaters that appear suddenly as a result of a posterior vitreous detachment often can be successfully treated with the laser procedure.

What happens during laser vitreolysis

Laser vitreolysis usually is pain-free and can be performed in an eye surgeon’s office. Just prior to the treatment, anesthetic eye drops are applied, and a special type of device (a gonioscope) is placed on your eye. Then, the surgeon will look through a medical microscope (a slit lamp) and deliver the laser energy to the floaters being treated.

During the procedure, you might notice dark spots. These are pieces of broken up floaters. The treatment can take up to a half hour, but it's usually significantly shorter.

At the end of the procedure, the gonio lens is removed, your eye is rinsed with saline and the surgeon will apply an anti-inflammatory eye drop. Additional eye drops may be prescribed for you to use at home.

Sometimes, you may see small dark spots shortly after treatment. These are small gas bubbles that tend to resolve quickly. There also is a chance that you'll have some mild discomfort, redness or blurry vision immediately after the procedure. These effects are common and typically won't prevent you from returning to your normal activities immediately following laser vitreolysis.

If you are bothered by large, persistent eye floaters, ask your optometrist if laser vitreolysis might be a good treatment option for you.

Remember, a sudden appearance of a significant number of eye floaters, especially if they are accompanied by flashes of light or other vision disturbances, could indicate a detached retina or other serious problem in the eye. If you suddenly see new floaters, see your optometrist immediately or go to your nearest eye hospital without delay.

Page published on Monday, 16 March 2020