Pigment dispersion syndrome

What is pigment dispersion syndrome?

When the eye’s lens and iris are too close together, they can rub against each other pretty frequently. This rubbing causes tiny bits of pigment to break free from the back of the iris and float through the eye in the aqueous humor. This is called pigment dispersion syndrome (PDS).

Everyone has a small amount of pigment dispersion, especially as we age. But the amount is much greater in PDS, and it begins earlier.

You won’t be able to feel it if your iris and lens rub together or if your eyes are losing pigment. And PDS typically won’t disperse enough eye pigment to change the color of your eyes. But an eye doctor may be able to see areas of lost eye pigmentation during an eye exam.

PDS seems to be most common in young adults (20-40 years old) who have myopia and light-colored eyes. But experts aren’t quite sure how common pigment dispersion syndrome actually is. Estimates for how many people may have the condition range from .014% of the population to 2.5% or more.

One big reason for this is that PDS — by itself — rarely causes any symptoms or vision problems. Another is that it’s more difficult to detect in darker-colored eyes. So it’s possible that pigment dispersion syndrome is underdiagnosed in general.

This is a problem because pigment dispersion syndrome can lead to serious eye disease. While PDS itself may not cause any noticeable symptoms, it is a common cause of secondary glaucoma.

This type of secondary glaucoma is called pigmentary glaucoma. PDS leads to pigmentary glaucoma often enough that many experts see them as degrees of the same disease.

What is pigmentary glaucoma?

Pigmentary glaucoma (PG) is damage to the eye’s optic nerve as a result of pigment dispersion syndrome.

Many things can damage the optic nerve. But when the damage is specifically related to intraocular pressure (IOP or eye pressure), it’s called glaucoma. Pigment dispersion syndrome can increase eye pressure by clogging the eye’s drainage system with too much pigment debris.

Most of the pigment debris flows through the eye in the aqueous humor and ends up in the trabecular meshwork. The trabecular meshwork is a part of the eye’s drainage system that acts sort of like a filter. Cells in this filter can “eat” quite a lot of cell debris. But eventually, they get overwhelmed and begin to die.

Over time, the increase in IOP can damage more and more of the optic nerve. This causes permanent vision loss and, without treatment, blindness.

There are three broad groupings along the pigment dispersion syndrome–pigmentary glaucoma spectrum:

PDS only – Signs of extra pigment dispersion are visible to a doctor during an eye exam, but IOP is still in a healthy range.

PDS with increased eye pressure – Pigment dispersion has led to ocular hypertension (high IOP), but there’s no optic nerve damage.

Pigmentary glaucoma – Pigment dispersion has led to high IOP and optic nerve damage. Vision loss may or may not be noticeable yet.

Approximately 35% to half of all people diagnosed with PDS develop pigmentary glaucoma. However, the progression to pigmentary glaucoma is about three times more common in males than in females. Males also tend to develop pigmentary glaucoma about 10 years sooner than females. In both, PG tends to develop decades earlier than other types of glaucoma.

Symptoms of pigment dispersion syndrome

In most cases, pigment dispersion syndrome doesn’t cause any symptoms.

Symptoms tend to come later and are caused by spikes in eye pressure. At this point, PDS has often already progressed to glaucoma.

When IOP increases slowly, it doesn’t cause noticeable symptoms. PDS raises pressure slowly as pigment builds up in the drainage system. This is what ultimately leads to glaucoma.

But it also causes sporadic, sharp increases in pressure. So the symptoms can be a lot like acute angle-closure glaucoma. Still, many people never have any symptoms.

Symptoms of IOP spikes can include:

Blurry vision

Colorful visual halos around lights

Headaches

Light sensitivity

Eye pain

Nausea

Eye redness

These symptoms tend to be intermittent. Many people only have them after exercise. Exercise itself can raise IOP, and it can also cause more pigment dispersion, which raises IOP even more. But non-strenuous activities can also trigger symptoms.

For example, blinking and certain head postures or movements can raise eye pressure. Pupil dilation and contraction when walking into and out of dark rooms can increase IOP as well as dislodge more pigment. In eyes with a higher baseline IOP, small pressure spikes have a bigger impact.

In rare cases, pigment dispersion syndrome can cause heterochromia. This is when one iris is a different color than the other. It may also cause eye color to become darker, but rarely a noticeable amount. However, both of these are usually due to pigment debris depositing on the front of the iris — not pigment loss. PDS usually affects both eyes about equally.

Often, people never experience any symptoms until they notice actual vision loss. At this point, pigmentary glaucoma is already in an advanced stage.

Clinical signs of pigment dispersion syndrome

PDS does not cause noticeable symptoms in most people, especially early on. But it does have clinical signs that an eye doctor can detect during an eye exam.

For example, an eye doctor can see if there is extra pigment debris in the front part of the eye. They can also see if the trabecular meshwork is discolored from collecting the pigment.

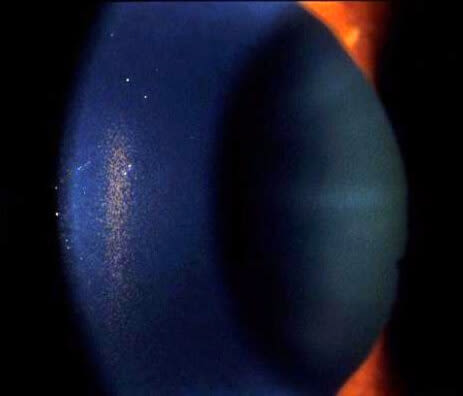

Magnified image of a Krukenberg spindle taken during a slit lamp exam. Click image to enlarge.

One of the more well-known signs of PDS is called a Krukenberg spindle. A Krukenberg spindle is a deposit of pigment on the inside surface of the cornea.

Blinking causes a pressure change in PDS eyes that propels aqueous humor up and toward the cornea. Some of the pigment debris in the aqueous gets stuck to the cornea as it hits and floats back down. Over time, more and more pigment sticks to the same spot in a vertical spindle shape. Krukenberg spindles aren’t visible to the naked eye, and they don’t affect vision.

An eye doctor may also be able to see areas of the iris that are losing pigment. However, they are not always detectable in dark-colored or thick irises.

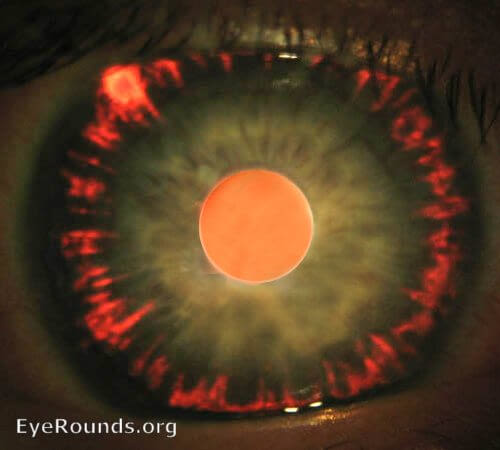

Iris transillumination defects. Click on image to enlarge. Photo courtesy of Andrew Doan, MD, PhD. EyeRounds.org, The University of Iowa.

These areas are called transillumination defects because doctors check for them by shining a beam of light sideways into the eye. The areas with pigmentation loss will allow more of the light to show through the front of the iris.

Other clinical signs can also be risk factors for pigment dispersion syndrome. Eye doctors can see certain anatomical traits in the eye that are common in PDS.

Each of these signs is detectable using non-invasive eye exam methods. Some are visible during a basic slit-lamp exam. Others are visible during a standard part of a glaucoma exam called a gonioscopy.

Your eye doctor will perform a gonioscopy if they see any signs of PDS during your yearly eye exam. They may also perform further glaucoma testing. Depending on what they see, they may recommend other tests to rule out other diagnoses.

It is possible for the signs of PDS to lessen later in life. This is sometimes called “burn out.”

However, these people often already have pigmentary glaucoma. Many of them may be misdiagnosed with primary open-angle glaucoma because the signs of active PDS are gone.

What causes the release of eye pigment?

Pigment dispersion occurs when the back of the iris rubs against the front of the lens.

The iris is the colored part of your eye, and the pigment is what gives it its color. The lens is a clear, ellipsoid-shaped structure that sits right behind the iris. It helps the eye focus by slightly changing shape depending on what you’re looking at.

When they are too close together, there can be a lot of contact between them. But why this contact happens and why it sometimes causes PDS is less clear.

The dominant theory is that some people are predisposed to PDS due to their eye anatomy. There are four anatomical traits that are very common in pigment dispersion syndrome:

Deep anterior chamber – The distance between the cornea and the front surface of the lens is longer than average.

Posterior iris insertion – The iris sits farther back in the eye than average.

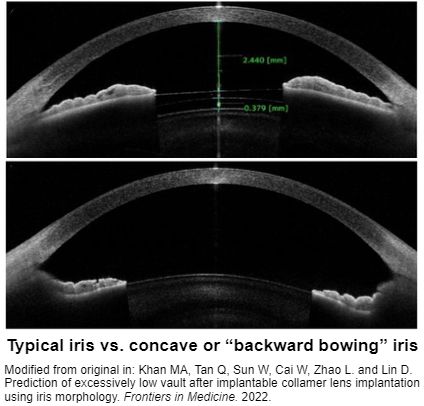

Concave-shaped iris – The iris bows backward toward the lens.

Flat cornea – The curvature of the cornea is flatter than average.

Usually, eye pressure is slightly higher in the back, behind the iris. But the combination of these four traits can make pressure higher in the front instead.

Click on image to enlarge.

The higher pressure in front of the iris pushes it into a concave shape — bowed backward toward the lens. This leads to a lot more contact and is the primary cause of pigment dispersion.

The concave iris can also act like a sort of "flap valve." This means things like blinking, focusing and changes in pupil size can pump fluid through the pupil into the front of the eye.

It can add just enough extra pressure in front of the iris to push it against the lens and keep it there. Eye doctors call this reverse pupillary block. It can lead to extreme spikes in IOP and nearly constant pigment dispersion.

Myopia (nearsightedness) is also very common among pigment dispersion syndrome patients. Myopic eyes are usually longer from front to back, which results in a deeper anterior chamber.

But iris bowing can’t explain all PDS. Some cases of PDS don’t exhibit any iris bow. And concave iris bowing occurs in other conditions and in healthy eyes without leading to PDS.

Researchers believe there are genetic components, but they haven’t found them all yet. For example, PDS can be inherited. But inheritance is sporadic and not predictable.

It is possible that the irises and/or the pigment endothelial cells in these eyes are genetically more prone to atrophy or degeneration.

Pigment dispersion syndrome treatment

PDS on its own doesn’t always need any treatment. However, it is still very important to have regular eye exams.

Your eye doctor needs to monitor your eye health and IOP closely to ensure treatment begins as soon as you need it. Up to 10% of patients develop pigmentary glaucoma within five years of the onset of their PDS.

Very rarely, eye doctors may recommend laser peripheral iridotomy (LPI) if a patient is at high risk for pigmentary glaucoma. LPI uses a laser to create a tiny hole at the edge of the iris. This can help balance pressure between the front and back of the eye.

In some cases, this may help prevent a future increase in IOP. However, LPI is only an option for patients under 40 who don’t already have elevated eye pressure. It doesn’t work as a treatment for pigmentary glaucoma or to lower IOP.

Pigmentary glaucoma treatment

Treatment typically begins when PDS progresses to ocular hypertension and/or pigmentary glaucoma. Eye doctors usually prescribe eye drops to lower IOP as the first step.

Prostaglandin analogue eye drops are often the first choice. These drugs work by helping more aqueous pass through the eye’s drainage channels. Other types of glaucoma eye drops, such as beta blockers and miotics, may also be options.

Beta blockers lower IOP by reducing the amount of aqueous the eye makes. However, in some people, this can lead to even more pigment debris remaining in the eye’s drainage channels. Miotics work by shrinking the pupil. This can significantly reduce how often the iris and lens rub together. But they also increase the risk of retinal detachment, which is already a higher risk in both PDS and myopia.

If prescription eye drops don’t control IOP well enough, the next step is often laser surgery. Selective laser trabeculoplasty (SLT) and argon laser trabeculoplasty (ALT) are very common types of glaucoma laser surgery. The surgeon uses a laser to open up better pathways in the trabecular meshwork.

Some patients may need conventional glaucoma surgery if their IOP stays too high even with eye drops and laser treatment. These types of surgery include trabeculectomy (also called filtering surgery) and several types of minimally invasive glaucoma surgery (also called MIGS).

LEARN MORE about types of glaucoma surgery

When to see a doctor

Pigment dispersion syndrome rarely causes any symptoms. Yearly eye exams are the best way to catch it early, before it can raise eye pressure. Waiting for symptoms of high IOP puts you at much higher risk for pigmentary glaucoma and permanent vision loss.

PDS is most common among 20-40-year-olds with myopia and light-colored eyes. People who have these risk factors may need comprehensive eye exams more than once a year.

If you do have any symptoms of high eye pressure, see an eye doctor right away. These may include blurry vision, colored halos around lights, eye pain, headaches and nausea. Symptoms of high IOP can come and go and may be worse after exercise.

Pigmentary glaucoma, revisited. Review of Optometry. March 2020.

Pigment dispersion syndrome. Digital Reference of Ophthalmology. Columbia University Irving Medical Center. Accessed July 2024.

Pigmentary glaucoma and pigment dispersion syndrome. EyeWiki. American Academy of Ophthalmology. December 2023.

Pigment dispersion syndrome: A brief overview. Journal of Clinical and Translational Research. October 2022.

Pigment dispersion syndrome and its implications for glaucoma. Survey of Ophthalmology. September–October 2021.

Pigment dispersion syndrome. StatPearls [Internet]. June 2023.

Pigment dispersion glaucoma. StatPearls. May 2023.

Genome-wide association study identifies two common loci associated with pigment dispersion syndrome/pigmentary glaucoma and implicates myopia in its development. Ophthalmology. January 2022.

What is pigment dispersion syndrome? EyeSmart. American Academy of Ophthalmology. May 2023.

What is glaucoma? In Glaucoma: What every patient should know. Wilmer Eye Institute, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine. Accessed July 2024.

Glaucoma. American Optometric Association. Accessed July 2024.

Genetic heritability of pigmentary glaucoma and associations with other eye phenotypes. JAMA Ophthalmology. January 2020.

Glaucoma and the importance of the eye's drainage system. BrightFocus Foundation. July 2021.

Pigmentary glaucoma and pigment dispersion syndrome. BrightFocus Foundation. July 2021.

Intraocular pressure. StatPearls [Internet]. February 2024.

Heterochromia. EyeSmart. American Academy of Ophthalmology. April 2024.

Secondary glaucoma: Toward interventions based on molecular underpinnings. WIREs Mechanisms of Disease. September 2023.

Eye anatomy: Parts of the eye and how we see. EyeSmart. American Academy of Ophthalmology. April 2023.

Why axial length matters. Review of Myopia Management. September 2023.

Comparison of anterior chamber angle parameters and iris structure of juvenile open-angle glaucoma and pigmentary glaucoma. Indian Journal of Ophthalmology. February 2022.

Current situation and progress of drugs for reducing intraocular pressure. Therapeutic Advances in Chronic Disease. December 2022.

Retinal detachment. National Eye Institute. November 2023.

Page published on Wednesday, August 14, 2024

Page updated on Tuesday, August 20, 2024

Medically reviewed on Saturday, July 13, 2024