Achromatopsia

What is achromatopsia?

Achromatopsia is a rare genetic eye disorder. It affects a person’s ability to see or distinguish colors (also known as color blindness). People with achromatopsia have a complete or partial lack of color vision. Other visual impairments are often present as well.

Achromatopsia is a condition that affects both eyes. It generally does not progress, meaning that a person’s vision typically does not worsen over time due to this disorder.

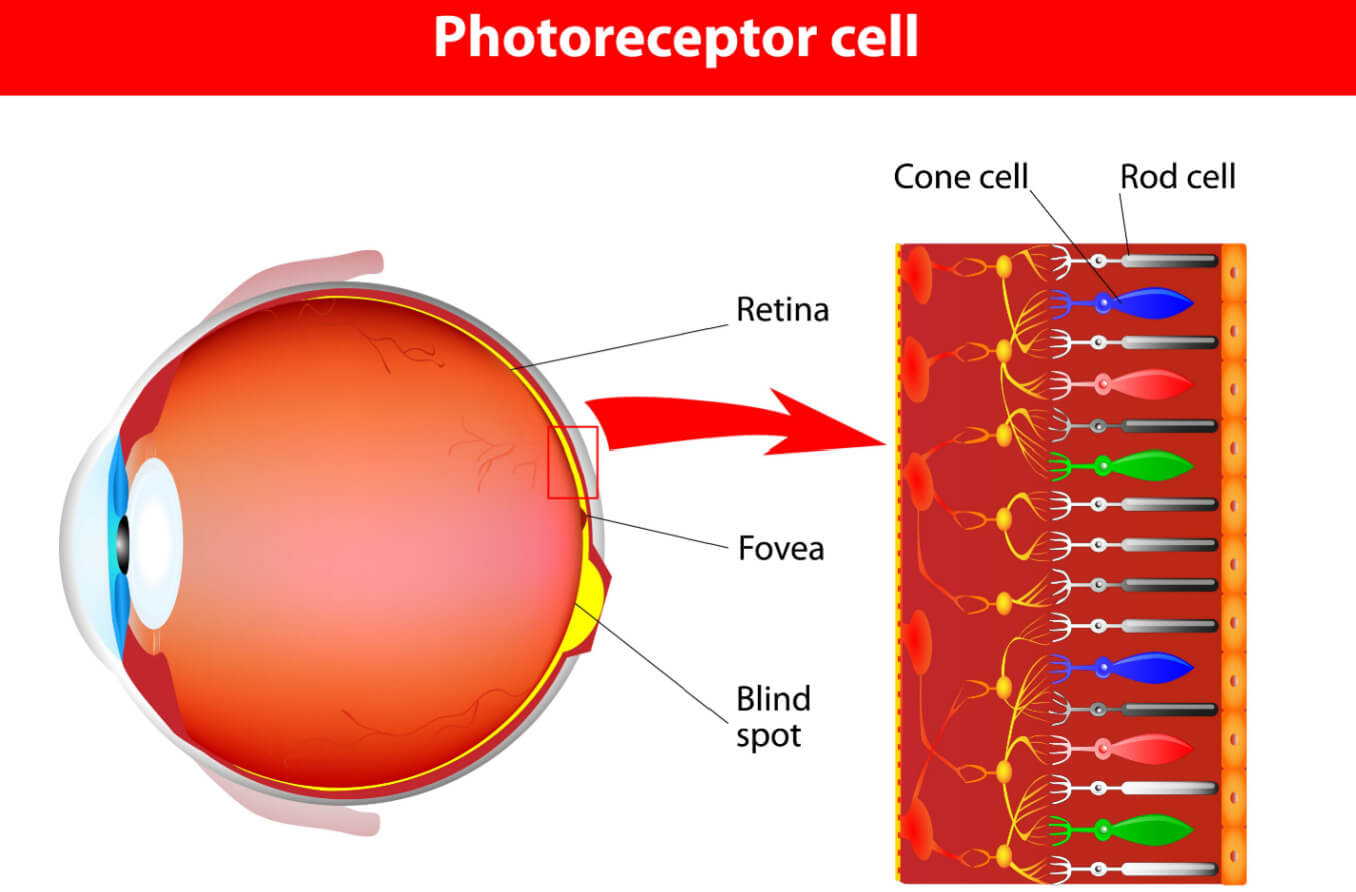

Like most types of color blindness, achromatopsia results from a problem within the retina. The retina is a light-sensitive membrane in the back of the eye that contains special cells called photoreceptors. These cells, which consist of rods and cones, convert light into signals that help the brain interpret the images a person sees. Rods help the eye to see in the dark and low light. Cones allow the eye to see in color vision.

There are three types of cones in the retina — those that detect red, green and blue. Color blindness occurs if one or more of these cone types are missing or defective. When achromatopsia is present, all three types of cone receptor cells are affected.

Most individuals with achromatopsia have complete color blindness. They see the world in black, white and gray. Those with incomplete achromatopsia may have a limited ability to visualize colors.

How common is achromatopsia?

Achromatopsia affects approximately 1 in 30,000 people around the world. It is more common in areas where marriages among close relatives are more likely to occur.

It is also more prevalent in Pingelap, a small group of islands in the eastern Pacific Ocean. As described in the Oliver Sacks book, “The Island of the Colorblind,” a typhoon in the 1700s affected the population of the islands. This left a small number of people to repopulate the area and caused the propagation of an achromatopsia-carrying gene.

Types of achromatopsia

There are two primary forms of achromatopsia: complete achromatopsia and incomplete achromatopsia.

Complete achromatopsia is the more common form of the condition. It is also referred to as rod monochromacy or total color blindness. With this type, individuals have no functioning cones and thus no color vision. They only see in black, white and shades of gray, and the eye must depend on rod functioning for vision. Those with complete achromatopsia tend to have more severe visual issues.

Incomplete achromatopsia is rarer and involves limited color vision. Colors may appear dull or may be harder to see. This is due to reduced cone function in the retina. Visual effects are similar but typically not as severe. With incomplete achromatopsia, the eye uses rods and limited-functioning cones to see.

What causes achromatopsia?

Achromatopsia passes from a parent to a child in an autosomal recessive hereditary manner. When a condition or trait is autosomal recessive, two copies of a mutated gene are present in an individual’s genetic makeup. One gene is from the mother and the other is from the father. Both parents must either be carriers of a mutated gene or have the condition to pass it on to a child. It is common for parents of a child with achromatopsia to each carry a copy of a mutated gene but show no signs of the disorder.

Achromatopsia is caused by mutations in one of six genes: ATF6, CNGA3, CNGB3, GNAT2, PDE6C and PDE6H.

Symptoms

People with achromatopsia may have symptoms that affect their eyes and vision. A person’s visual acuity can also vary according to the severity of the condition. Patients with complete achromatopsia have a visual acuity of 20/200 or lower. Those with incomplete achromatopsia may experience vision as high as 20/80. Far-sightedness is also a common symptom.

Some signs and symptoms of achromatopsia may be noticeable shortly after birth. Other indications of the condition might not become apparent until early childhood. Common signs and symptoms of achromatopsia include:

Light sensitivity (photophobia)

Rapid and repetitive eye movement (nystagmus)

Farsightedness (hyperopia)

Nearsightedness (myopia)

Color blindness

Blind spots (scotomas)

Glare

Difficulty seeing in bright light (hemeralopia)

Nystagmus may develop within the first few months of a child’s life and is often the first symptom to occur. Symptoms may be less severe in individuals with incomplete achromatopsia.

Diagnosis

Achromatopsia is typically diagnosed by an ophthalmologist. The process begins with a review of the individual’s medical history, family history and symptoms. Several exams and techniques may be used to diagnose the condition.

Eye exam

A general eye exam is performed to assess the patient’s eye health and visual acuity. This includes a fundoscopic exam to evaluate the retina. It may also include peripheral (visual field) and color vision testing.

Electroretinogram (ERG)

ERG is a key technique for diagnosing achromatopsia. This test measures electrical currents in the retina to evaluate how the photoreceptors respond to light.

Optical coherence tomography (OCT)

OCT produces images of the retina. It allows ophthalmologists to assess the structure of dysfunctional cones. Physicians can also determine the stage of the condition based on this information.

Fundus autofluorescence imaging (FAF)

FAF uses a blue light to look for any deterioration in the rods, cones and other cells within the retina.

Genetic tests

Genetic testing may also be performed to confirm an achromatopsia diagnosis. Knowing the hereditary factors behind this condition can help parents understand the likelihood of passing it on to future children.

Treatment and management

At this time, there is no cure for achromatopsia. However, clinical trials might be available for individuals affected by the condition. These studies may involve observation to help researchers better understand the condition, gene replacement therapy (for CNGA3 and CNGB3 mutations) or other factors. Additional information can be obtained by visiting clinicaltrials.gov.

Treating achromatopsia involves managing its symptoms and optimizing vision as much as possible. This may include one or more of the following modalities:

Corrective lenses for refractive errors (including hyperopia, myopia and astigmatism)

Low vision devices and aids (such as magnifying lenses and assistive technology)

Dark- or red-tinted lenses to decrease photosensitivity (glasses might wrap around the eyes and contain a top shield to reduce light exposure)

Color blind glasses may enhance color vision in individuals with red-green color deficiencies.

Nutritional support for the eyes with a diet rich in leafy greens and fruit

Routine eye exams should also take place every six to 12 months for children. All adults aged 18 and over should have eye exams every year. But adults who have achromatopsia may need to have exams more often.

Further support may be obtained by visiting the Achromatopsia Group.

When to see a doctor

The visual effects of achromatopsia can negatively impact a child’s development. It is, therefore, important to seek a medical evaluation when signs or symptoms occur. For many, this includes rapid eye movement or light sensitivity. These signs may appear within the first few months of a child’s life. Other effects, such as low vision or color blindness, might not occur until later in childhood.

Parents concerned about the possibility of passing achromatopsia to unborn or future children should seek genetic counseling, prenatal testing and other forms of family planning.

READ NEXT: Tips for living better with color blindness

Achromatopsia. American Academy of Ophthalmology. EyeWiki. November 2022.

Achromatopsia. American Association of Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus. March 2022.

Retina. Cleveland Clinic. April 2022.

Cones. American Academy of Ophthalmology. EyeSmart. December 2018.

What is color blindness? American Academy of Ophthalmology. EyeSmart. September 2022.

Achromatopsia. GeneReviews [Internet]. September 2018.

Achromatopsia. Cleveland Clinic. July 2022.

Achromatopsia: Genetics and gene therapy. Molecular Diagnosis & Therapy. December 2021

Autosomal recessive. A.D.A.M. Medical Encyclopedia [Internet]. Ebix, Inc. MedlinePlus.gov. January 2022.

Achromatopsia: for professionals. Gene Vision. December 2020.

Comprehensive adult eye and vision examination, second edition. American Optometric Association. January 2023.

Page published on Tuesday, April 4, 2023

Page updated on Tuesday, April 11, 2023

Medically reviewed on Tuesday, March 28, 2023