Retinal dystrophy

What is inherited retinal dystrophy (IRD)?

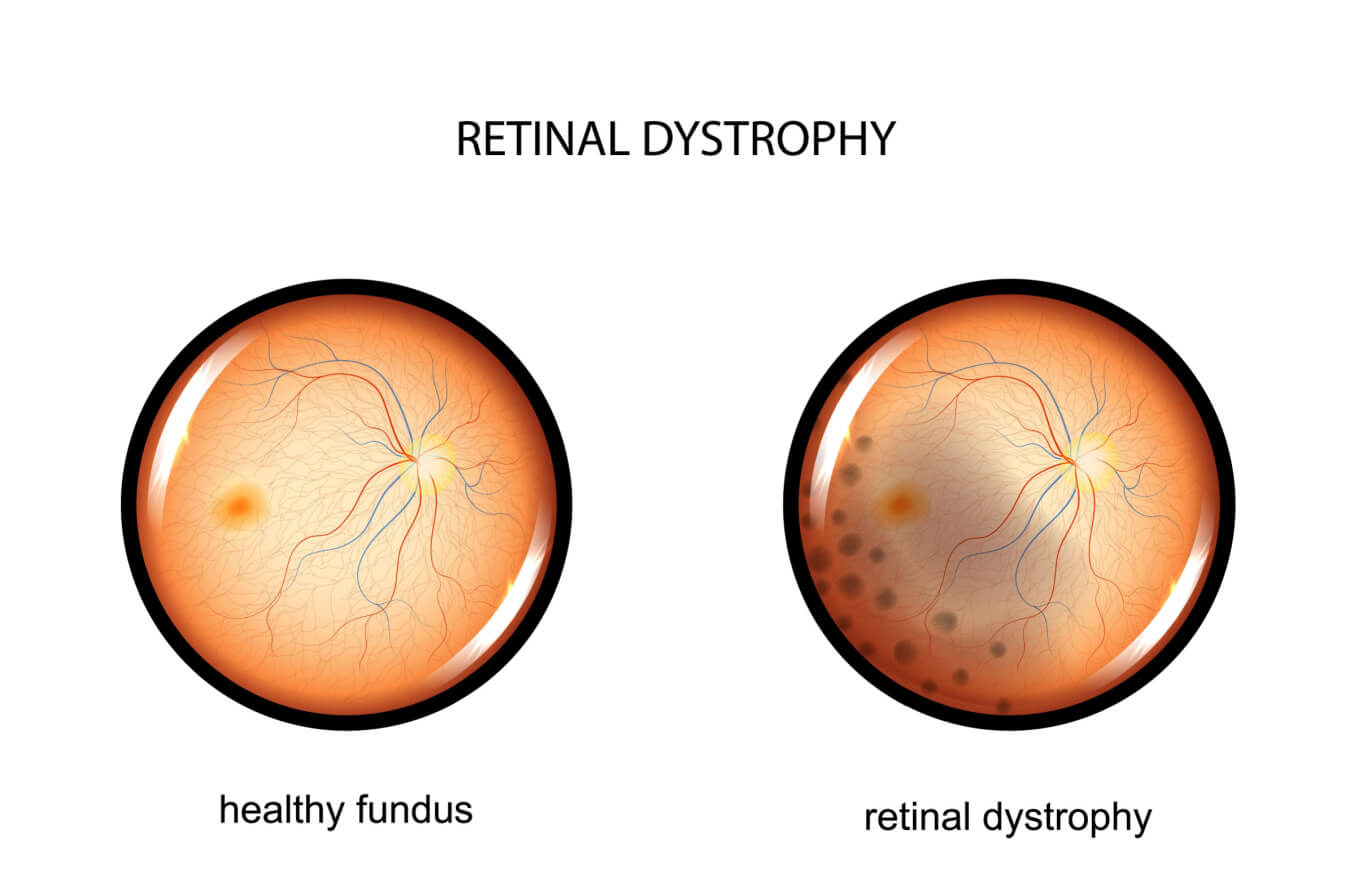

Retinal dystrophies are rare, inherited eye diseases resulting from an abnormality in a person’s genes. They cause progressive damage to the light-sensitive tissue at the back of the eye — the retina. Common symptoms include decreased visual acuity, color vision, night vision and peripheral vision.

Some retinal dystrophies are limited to the retina and only affect vision. But, some are linked with other conditions that affect the body, such as hearing loss or kidney disease.

In people with retinal dystrophy, the cells of the retina do not function properly. And this causes a wide range of vision issues. Retinal dystrophies are often diagnosed during childhood. Many IRDs progress slowly but are degenerative, meaning that vision can continue to decrease over time. Symptoms can range from mild impairment to severe vision loss and blindness.

There are many types of inherited retinal dystrophies. The most common include retinitis pigmentosa, cone–rod dystrophy, Stargardt disease, Leber congenital amaurosis and choroideremia.

What causes hereditary retinal dystrophy?

Inherited retinal dystrophies are caused by variations in a person’s genes, leading to improper functioning of the retina. Researchers have already found more than one hundred genes linked to retinal dystrophies and continue to find more.

The genes that cause IRD are usually passed down from parents, sometimes even skipping a generation. If retinal dystrophy runs in the family, symptoms and severity can vary with each family member. Genetic testing is available to help diagnose the disease. It can also help determine how likely it is that the condition will be passed down to future generations.

Not all cases of IRD are inherited from parents. In some instances, the condition occurs due to a new genetic mutation during a baby’s development.

Symptoms

There are many different types of retinal dystrophy caused by many different genes. Each has different signs and symptoms and progress at different rates. Most IRDs lead to degeneration of the retina and decreased vision over time, although they often progress slowly.

Diagnosis

Doctors use many different types of tests to determine if someone has retinal dystrophy and what type.

These tests include:

Comprehensive eye exam – Includes visual acuity, contrast sensitivity testing, color vision testing and examination of the health of the eye

Peripheral vision test – Measures side vision and looks for blind spots (scotomas)

Photos of the back of the eye – Allow doctors to analyze and document the back of the eye

Electroretinogram – Measures the electrical response of the rods and cones of the retina, allowing doctors to determine if they are functioning correctly

Optical coherence tomography – Provides high-quality 3D images of cross-sections of the retina

Fundus autofluorescence imaging – Takes pictures of the retina using the fluorescent properties of a pigment called lipofuscin, providing information on the health of the retina

Genetic testing – Provides information about an individual’s genes

The earlier that retinal dystrophy is accurately diagnosed, the higher the chances that doctors can slow down the degeneration of the retina and vision loss.

Treatment and management

Current treatments aim to slow the progression of vision loss. Gene therapy options are offered by some institutions. This provides doctors with new ways to help people with retinal dystrophies.

Genetic testing allows individuals to learn whether they have RPE65-associated retinal degeneration. If they do, they may be eligible for treatment with Luxturna™ gene therapy. This was approved in 2017 by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

The treatment is effective for people with a mutation in both copies of the RPE65 gene. It’s important to receive this treatment as soon as possible after diagnosis.

Luxturna™ works by delivering a healthy, working copy of the RPE65 gene into the retina by injection. The procedure is done under anesthesia. Luxturna™ can improve night vision and help patients better navigate low-light conditions. It costs $850,000 for both eyes, although it may be covered by insurance.

Clinical trials of gene and stem cell therapies are ongoing. Speak to your doctor about trials in your area.

An appointment with a vision rehabilitation doctor may also be beneficial. Tinted glasses, magnifiers and assistive technology can enhance visual comfort and visual function for many people.

Retinitis pigmentosa (RP)

Retinitis pigmentosa is a group of inherited retinal dystrophies that affect the ability of the retina to perceive light. It is rod–cone dystrophy, meaning that rods break down first, followed by cones. This is why night vision is affected before central vision.

RP is the most common form of rod–cone dystrophy. Symptoms begin during the first or second decade of life and progress over time.

Symptoms of retinitis pigmentosa typically follow the following progression:

Night vision loss – Difficulty seeing in the dark or dim light is often the first symptom

Peripheral vision loss – Gradual loss of side vision

Central vision loss – Difficulty seeing details, reading, recognizing people, driving

Color vision perception issues – In some cases, color vision can be affected

Cause

RP can cause the photoreceptor cells — rods and cones — as well as the connections between the cells of the retina to break down over time. Mutations in more than 60 different genes can cause this disease, resulting in variations in the severity and rate of vision loss.

Retinitis pigmentosa can occur alone or as part of another medical issue. One example is Usher syndrome, which affects both hearing and vision. Less commonly, retinitis pigmentosa can be caused by infections, medication or injury to the eye.

Prognosis

Retinitis pigmentosa causes a slow, progressive decline in vision. Genetic testing is essential because it can identify which genetic mutations are causing the disease. Identifying the gene mutation can determine whether a person is eligible for certain treatments or clinical trials.

Individuals who are diagnosed early may be eligible for treatments such as Luxturna™ gene therapy. Retinal implants may be an option for individuals with advanced retinitis pigmentosa.

Additional therapies are in development and show promise. There is slight evidence that vitamin A may be beneficial for some forms of RP. But it must be taken with caution because too much vitamin A can cause liver issues. In addition, lutein supplements and fish oil may provide nutritional support. Speak to your eye doctor for their recommendation.

Cone–rod dystrophy

Cone–rod dystrophy is a group of more than 30 types of inherited retinal dystrophies. These conditions typically cause cones to degenerate before rods. This leads to central vision loss and increased light sensitivity (photophobia).

This is different from rod–cone dystrophies, such as retinitis pigmentosa. In a rod–cone dystrophy, the rods break down before the cones (with symptoms such as night blindness occurring first).

In cone–rod dystrophies, over time, color vision is affected, and blind spots begin to appear in central and side vision. Eventually, rods begin to break down, causing peripheral vision to be affected and night blindness to develop. In some cases, nystagmus — involuntary eye movements — can also develop.

Cone–rod dystrophies are usually diagnosed in childhood. They can affect only the eyes or occur as part of a condition that affects other parts of the body as well.

Cause

Cone–rod dystrophies are a genetic disorder. These conditions can be inherited in several different ways:

Autosomal recessive – Both parents carry a copy of the mutated gene (most common)

Autosomal dominant – One parent carries a copy of the mutated gene

X-linked recessive – The mutated gene is located on a sex chromosome (XY for males, XX for females)

Prognosis

The severity of symptoms and rate of progression varies by type. Many individuals with cone–rod dystrophy will experience visual difficulties by mid-life. Symptoms can begin to appear any time from childhood to adulthood. Individuals typically begin to experience some loss of visual function beginning in childhood. Speak to your eye doctor about the latest treatments and clinical trials.

Stargardt disease

Stargardt disease is also called juvenile macular dystrophy or fundus flavimaculatus. It is the most common form of inherited macular degeneration.

Stargardt disease causes the photoreceptor cells in the central portion of the retina — the macula — to break down. The macula provides detailed central vision, which is important for reading, driving and recognizing people.

Due to this, individuals with Stargardt disease may begin to struggle with tasks that require sharp visual acuity. They may also struggle to adjust from brightly lit areas to dimly lit areas.

Cause

A naturally occurring pigment in the retina called lipofuscin builds up in cells beneath the macula. Over time, accumulation of this fatty, yellow pigment can damage the macula and fovea (the center part of the macula) and impair vision.

Stargardt disease can be caused by different inheritance patterns. When the mutation of the ABCA4 gene causes the condition, it is inherited in an autosomal recessive pattern. When the condition is caused by a mutation of the ELOVL4 gene, it is inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern.

Genetic testing is important for individuals experiencing a progressive loss of central vision and visual acuity so that the condition can be accurately diagnosed.

Prognosis

The symptoms of this disorder usually appear in childhood to late adolescence and progress over time. The rate at which vision worsens can vary. In some cases, the disease progresses slowly but then enters a period in which vision declines quickly and then finally levels off.

Many people stabilize around 20/200. In general, peripheral vision usually remains, although night vision and color vision can also be affected.

Research into gene therapy is ongoing. Doctors recommend that individuals avoid smoking or taking vitamin A supplements, as this may worsen the disease. Vision rehabilitation can improve visual function and quality of life. Simple lifestyle adjustments such as wearing sunglasses can improve comfort and prevent harmful ultraviolet (UV) rays from reaching the retina.

Leber congenital amaurosis (LCA)

Leber congenital amaurosis is a rare inherited eye condition that causes severe visual impairment at birth. Other vision issues, such as extreme farsightedness, nystagmus, light sensitivity and abnormal pupil reactions to light, are also associated with LCA.

Children with this condition are known to rub and poke at their eyes. It’s possible this contributes to the deep-set eyes associated with this disorder. Early socialization and educational intervention are important for preventing social isolation and developmental delays in these children.

Cause

More than 20 gene mutations can result in LCA. These mutations affect how the retina develops and functions, leading to profound vision loss at birth. The condition can be passed down by either autosomal recessive or autosomal dominant inheritance patterns.

Prognosis

Most children are born with severe vision loss, typically 20/400 or below. One-third are not able to perceive light. Studies have found that vision remains stable in most cases.

Depending on the gene mutation, gene therapy may be explored. In addition, it is important to provide vision rehabilitation and ensure that the child has plenty of socialization and educational opportunities.

Choroideremia

Choroideremia mostly affects males, causing vision loss that is progressive. Night blindness is often one of the first symptoms and is often diagnosed in childhood. This is followed by the development of tunnel vision, decreased central visual acuity, color vision loss and blindness in late adulthood.

Cause

Choroideremia causes atrophy, or wasting away, of the retina and the network of blood vessels that support it. Mutation of the CHM gene causes this condition. It is inherited in an X-linked recessive pattern. This means that it is passed on by the mother, who does not often have many signs or symptoms herself.

Prognosis

Peripheral vision loss and night blindness occur first. The field of vision continues to narrow, eventually affecting central vision and resulting in blindness in later adulthood, often when a person is in their 50s to 70s. The rate of vision loss varies with each individual. Research into gene therapy is ongoing.

Less common inherited retinal diseases

Although retinal dystrophies are not very common in general, the ones discussed above tend to be the most common in the category. Less common inherited retinal dystrophies exist as well, including:

Juvenile Best disease (Best vitelliform macular dystrophy) – Affects the macula (central, detailed vision) with abnormal accumulation of retinal pigment

Adult vitelliform foveomacular dystrophy (adult vitelliform degeneration) – Similar to Best disease, but occurs in adulthood and does not progress

Congenital achromatopsia – Causes a total loss of cone function, causing poor visual acuity, light sensitivity and severe loss of color vision

Congenital monochromatism – Causes color blindness due to normal rod function but no cone function or the presence of only one functioning cone

X-linked retinoschisis – Causes the layers of the retina to split, leading to poor visual acuity and, in some cases, affecting peripheral vision; typically affects young males

Familial drusen – Causes the development of yellow deposits under the retina, called drusen, which can lead to decreased central vision in later adulthood

Congenital stationary night blindness – Affects the rods, leading to difficulties with night vision

Alport's syndrome – A disorder that causes kidney disease, hearing issues, and eye and vision abnormalities

When to see a doctor

Routine comprehensive eye exams provide the best way to ensure healthy eyes and clear vision. If you are experiencing eye pain or notice a decrease in your central or peripheral vision or any other changes, it is important to see a doctor right away.

If you, or your child, have been diagnosed with retinal dystrophy, it is essential to continue following up with your medical care team. Following up on all appointments and testing is the best way to ensure the health of your eyes.

Retinal dystrophy causes, symptoms, and treatments. University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC). Accessed April 2023.

Inherited retinal disorders. Massachusetts Eye and Ear. Accessed April 2023.

Kellogg offers new gene therapy options for treating inherited retinal dystrophies. University of Michigan Kellogg Eye Center. Accessed April 2023.

Retinal dystrophy. University of Michigan Kellogg Eye Center. Accessed April 2023.

New treatments for retinitis pigmentosa. American Academy of Ophthalmology. August 2021.

Retinitis pigmentosa. Johns Hopkins Medicine. Accessed April 2023.

Retinitis pigmentosa. National Eye Institute. March 2022.

What Is retinitis pigmentosa? American Academy of Ophthalmology. September 2022.

New treatments for retinitis pigmentosa. American Academy of Ophthalmology. August 2021.

Cone–rod dystrophy. MedlinePlus Genetics. March 2018.

Cone–rod dystrophy. Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center. February 2023.

Stargardt disease. Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center. February 2023.

What is Stargardt disease? American Academy of Ophthalmology. December 2022.

Leber congenital amaurosis. MedlinePlus Genetics. October 2022.

Leber congenital amaurosis. EyeWiki. American Academy of Ophthalmology. April 2023.

What is choroideremia? Foundation Fighting Blindness. Accessed April 2023.

Choroideremia. EyeWiki. American Academy of Ophthalmology. June 2022.

Retinal dystrophies. StatPearls. March 2023.

Page published on Tuesday, May 2, 2023

Page updated on Tuesday, May 9, 2023