Blue sclera: Definition, causes and associated conditions

What is blue sclera?

Blue sclera is a condition in which the white part of the eye (sclera) has a blue, gray or purplish tint. In many cases, blue tint in the sclera occurs as a symptom of an underlying condition, or as a reaction to certain medication.

One or both eyes may have a bluish sclera, and it’s usually not painful. Depending on the cause, blue in the whites of the eyes may be visible at birth or may become noticeable later on in life.

Having a blue sclera is relatively harmless and no cause for alarm. However, it could be a symptom of a more serious underlying condition. If you notice a sudden change in sclera color, see an eye doctor. They can examine your eyes, determine the cause and offer treatment options.

What causes blue tint in whites of eyes?

The sclera is a thick connective tissue made up of different types of collagen and proteins. It works as a protective layer and extends from the cornea at the front of the eye, to the optic nerve at the back of the eye.

In a healthy eye, the sclera is white and smooth. When a sclera has a bluish tint, it’s often caused by thinning of the sclera. Thinness or transparency of scleral tissue makes the uvea, located beneath the sclera, and blood vessels more visible.

Essentially the blue tint in the white part of the eye is really the layers below the sclera peeking through the tissue.

Causes of scleral thinning often have to do with conditions that affect bone or connective tissue development. Other causes include anemia or similar iron deficiencies, certain medications, and exposure to silver compounds.

SEE RELATED: Pinguecula: Causes, symptoms and treatment

Conditions associated with a bluish sclera

Usually if a child is born with blue sclera, it’s due to a genetic disorder that affects the scleral tissue. Below are some conditions — both genetic and acquired — that could contribute to a blue sclera.

Osteogenesis imperfecta

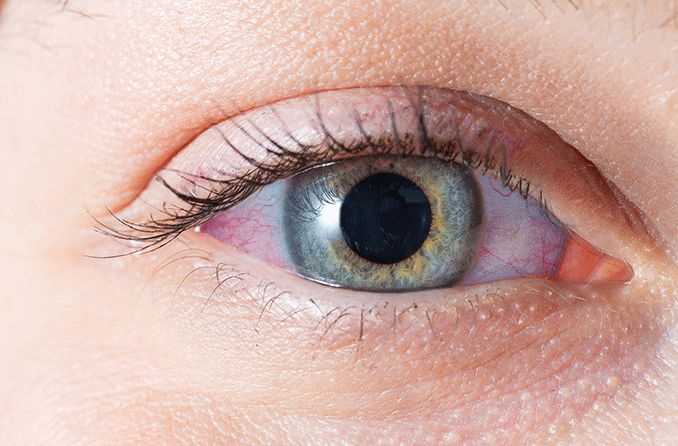

Blue sclera in a patient with osteogenesis imperfecta. [Image credit: Osteogenesis imperfecta. Permission granted by © 2022 American Academy of Ophthalmology]

The most common cause of blue sclera is osteogenesis imperfecta, otherwise known as brittle bone disease. It’s a genetic condition caused by a mutation in the gene that produces collagen.

Collagen is a key part in building strong bones. Because the sclera is also made of collagen, a lack of it — or having collagen that doesn’t work as it should — causes the sclera to be weaker or thinner than normal.

There are different types of osteogenesis imperfecta. The types categorize the varying symptoms presented and their severity. People with the disease have bones that are weak and, in some cases, misshapen.

READ NEXT: What is ochronosis?

Anemia or iron deficiency

Someone with chronically low iron levels can experience a bluish tint to the sclera. This can affect adults, as well as babies who are born with low iron.

Iron is an important part of the collagen production process. Studies found that collagen development is actually impaired when iron levels are low. When collagen isn’t being produced normally, it can cause the sclera (which is made of collagen) to thin and weaken.

Oculodermal melanocytosis (ODM)

Also known as nevus of Ota, this condition is characterized by excessive pigmentation in the uvea, sclera, episclera and eyelids. This results in a bluish gray tint in the sclera and eyelids.

While this condition is not dangerous at face value, having it significantly increases one’s risk of developing uveal melanoma. In fact, experts look at ODM as a precursor to uveal melanoma.

If you’ve been diagnosed with ODM, it’s critical that you protect your eyes from UV exposure and get regular eye exams to manage the health of your eyes.

SEE RELATED: Ocular melanosis

Marfan syndrome

Like many other conditions associated with a blue sclera, Marfan syndrome affects the body’s connective tissue. Connective tissue keeps the organs, cells and tissues together. It’s relied on heavily for proper growth and development.

In addition to vision problems such as high myopia, exotropia and other abnormalities, Marfan syndrome can cause the whites of the eyes to appear blue or gray.

Pseudoxanthoma elasticum

Though rare, it’s possible for a blue sclera to result from pseudoxanthoma elasticum. This is a genetic disease in which elastic body tissue becomes calcified.

The skin and cardiovascular system are usually affected most, as well as the retina. However, cases of blue-tinted scleras have been reported in association with the disease.

Kabuki syndrome

This is a genetic disorder that results from a mutation in genes KMT2D and KDM6A. Though the symptoms and their severity vary among those affected, Kabuki syndrome can cause growth delays, skeletal abnormalities, distinctive facial features and intellectual disability.

Facial features seen in Kabuki syndrome include long openings between the eyelids (palpebral fissures) and a droopy upper eyelid (ptosis). Blue sclera is also a symptom.

Addison’s disease

Addison’s disease is a rare disorder in which the adrenal gland doesn’t create enough cortisol and aldosterone. These are some of the most important hormones that the body makes.

One of the many symptoms involved with the condition is hyperpigmentation in and around mucus membranes. This often includes the eyes and gums.

Alkaptonuria

Also known as “Black Urine disease,” Alkaptonuria is a rare disorder that affects the body’s ability to break down tyrosine and phenylalanine. These are two important amino acid proteins. Since the amino acid can’t be broken down, a build-up of homogentisic acid occurs in the body.

The build-up of homogentisic acid can cause urine to appear dark and many health problems throughout a person’s life. This includes having grayish blue or brown spots in the sclera, a blue tint to cartilage in the ear, and issues with the bones and joints.

Ehlers Danlos syndromes

Ehlers Danlos syndromes is an umbrella term for a collection of genetic disorders that affect the connective tissue. More specifically, these disorders inhibit the production of collagen.

The most common presentation of these disorders is hypermobility (being “double jointed”) and having stretchy or loose skin. Because there’s a lack of collagen production, it’s also common for scleras to be thin. This results in a bluish tint in the sclera.

SEE RELATED: Subconjunctival hemorrhage (blood in eye)

Medications that can cause blue sclera

Developing blue sclera as an older adult — meaning the condition was acquired — usually means it’s caused by something in your medicine cabinet, not a genetic disease. Below are some medications that have been known to cause a blue tint in the sclera.

Talk to your doctor about the side effects you’re experiencing from your medication. Usually adjusting your dosage or finding an alternative treatment will help resolve the problem.

Minocycline

Minocycline is used to treat bacterial infections, including pneumonia and urinary tract infections. One of the side effects of this medication is changes in skin, teeth, gum and nail color.

If someone who is taking this medicine has a blue tint to their sclera, they may also have a blue tint to their nail beds.

Antipsychotics

Antipsychotics are prescribed to treat certain mental illnesses. These include schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, depression and certain personality disorders. Phenothiazines, which is a group of antipsychotic medications, may cause blue sclera.

Amiodarone

Amiodarone is a drug that treats cardiac problems, like arrhythmia (irregular heartbeat). When taking this drug, it’s possible for it to accumulate in the skin. This results in a blue-gray tint on the face, hands and eyes.

Phenytoin

Phenytoin is a seizure medication that has been reported to cause blue discoloration of the skin and eyes. Besides blue sclera, patients also have blue nail beds, lips and conjunctiva. Permanent vision changes were also reported.

Mitoxantrone

Mitoxantrone is a chemotherapy drug that is administered intravenously. Approximately 10%-29% of patients experience a bluish or greenish discoloration of the sclera and urine after treatment.

This side effect usually lasts one to two days after treatment.

SEE RELATED: Eye problems? Medications may be the culprit

When to see a doctor

Usually, having a sclera with a blue tint is not an immediate threat. Especially if you’ve been diagnosed with a genetic condition in which blue sclera is a symptom.

Sudden onset of blue sclera is still no cause for alarm, but an eye exam is recommended. An eye doctor can take a look and determine the cause of the change.

If you have any sudden changes in your vision, like blurriness or light sensitivity, or the whites of your eyes have turned yellow, you need to see a doctor. You should also see a doctor if the change in scleral color is accompanied by pain, irregular eye discharge or swelling.

READ MORE: Scleritis

Blue sclera and osteogenesis imperfecta — A rare association. Kerala Journal of Ophthalmology. January 2018.

The whites of my eyes have turned blue! American Academy of Ophthalmology. March 2007.

Unilateral bluish sclera. Indian Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism. November 2018.

Sclera: Definition, anatomy & function. Cleveland Clinic. November 2021.

Osteogenesis imperfecta (brittle bone disease). KidsHealth. April 2022.

Answer to photo quiz: Blue sclerae: diagnosis at a glance. The Netherlands Journal of Medicine. June 2016.

Oculodermal melanocytosis: Not to be overlooked. Retina Today. October 2017.

Marfan syndrome. The Marfan Foundation. Accessed July 2022.

Marfan syndrome. National Organization for Rare Disorders. 2021.

Pseudoxanthoma elasticum. EyeWiki. American Academy of Ophthalmology. July 2022.

Kabuki syndrome. National Organization for Rare Disorders. 2019.

Addison’s disease. National Organization for Rare Disorders. 2018.

Alkaptonuria. National Health Service. March 2022.

Ehlers Danlos syndromes. National Organization for Rare Disorders. 2017.

Minocycline. MedlinePlus. August 2017.

Antipsychotic medicines. Patient. June 2018.

Skin pigmentation, a rare side effect of chlorpromazine. Canadian Psychiatric Association Journal. April 1965.

“Blue-grey syndrome” – A rare adverse effect of amiodarone. Cor et Vasa. December 2018.

New antiepileptic medication linked to blue discoloration of the skin and eyes. Therapeutic Advances in Drug Safety. November 2014.

Mitoxantrone. Chemocare. Accessed July 2022.

Page published on Wednesday, July 27, 2022

Medically reviewed on Monday, July 18, 2022