Lucentis Vs. Avastin: A Macular Degeneration Treatment Controversy

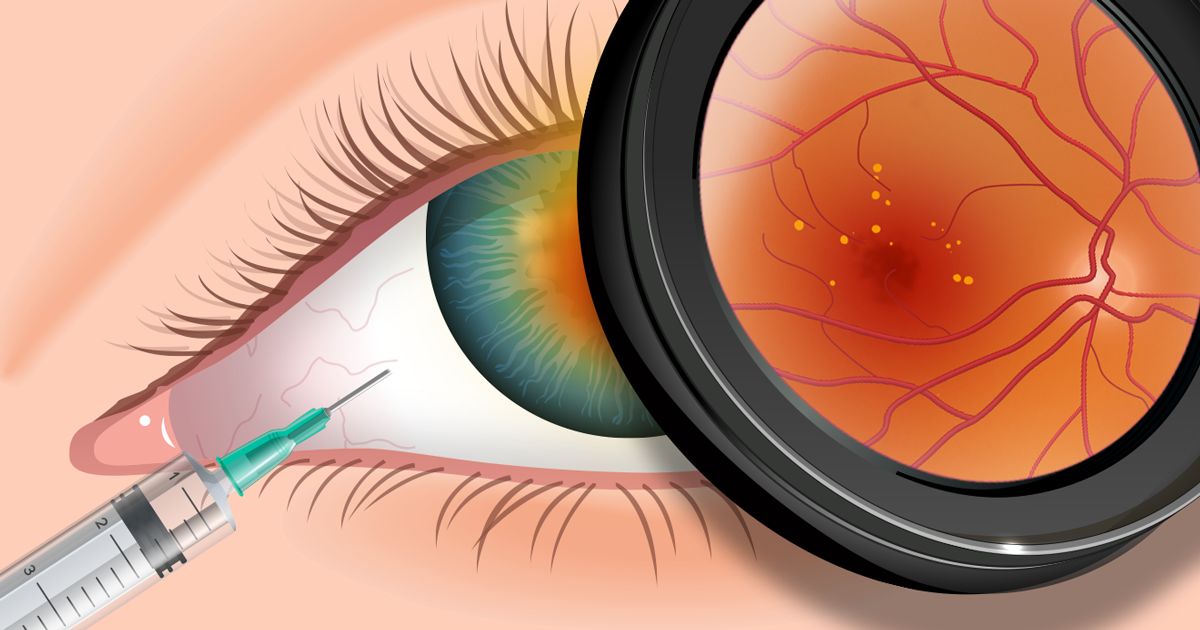

When Lucentis (ranibizumab) received FDA approval in late June 2006, the new macular degeneration drug was celebrated as a major medical breakthrough.

With about 200,000 new cases of advanced, age-related macular degeneration (AMD) identified each year in the United States*, many older Americans with more severe or "wet" forms of AMD endured inevitable, gradual loss of central vision.

Now, there is new hope for many who once faced certain blindness. Lucentis in clinical trials has been shown to stop and, in many cases, reverse at least some vision loss in most people with advanced AMD. These positive findings clearly make Lucentis by far the most effective FDA-approved treatment currently available for more damaging forms of AMD.

But some eye doctors argue that a drug closely related to Lucentis, known as Avastin (bevacizumab), also has been shown to be a highly effective and far cheaper alternative for lower-income individuals with advanced AMD. The problem is that Avastin is FDA-approved only for treatment of colon and other cancers, but not for macular degeneration. As an alternative, many eye doctors have been using Avastin as an off-label treatment.

Genentech Restricts Sales Of Avastin For Ophthalmic Uses

In October 2007, the company that markets both Lucentis and Avastin announced a strategy that was supposed to limit availability of Avastin for ocular uses.

The company, Genentech, cited safety issues as the reason for halting sales of Avastin to compounding pharmacies that have been dividing Avastin into the smaller quantities needed for treating the eye.

Genentech later responded to widespread protests from eye doctors and organizations including the American Academy of Ophthalmology (AAO) by announcing that Avastin can still be sold directly to physicians and delivered to destinations of their choice — including compounding pharmacies.

At an emotionally charged AAO conference session in November 2007, eye doctors protested the original decision that they say could have severely reduced supplies of Avastin and deprived lower income individuals of a sight-saving drug.

Genentech officials say they will not interfere with a physician's choice to prescribe Avastin for ophthalmic uses. But while the drug still can be sold to physicians, eye doctors say only compounding pharmacies can deal with sterility issues involved with repackaging Avastin for injection into the eye.

Eye doctors at the AAO conference said they have seen no evidence that the FDA has expressed specific concern about off-label use of Avastin.

Joshua Wenderoff, spokesman for the International Academy of Compounding Pharmacists (IACP), told reporters at the AAO meeting he disputes Genentech's claim that the decision to stop sales of Avastin to compounding pharmacies was based on safety concerns.

"We believe Genentech is putting profit ahead of patients," Wenderoff said.

Genentech's president of product development, Susan Desmond-Hellmann, MD, defended her company's position, saying that an FDA inspector asked numerous questions about the propriety of Genentech's direct sales of Avastin to compounding pharmacies and its off-label use as an ophthalmic drug.

"We stand behind the decision we made," Desmond-Hellman said.

Genentech officials say they work very closely with any individuals who might face economic hardship from use of Lucentis, including providing referrals to charitable organizations or other agencies offering assistance. Questions regarding economic assistance will be answered at this toll-free number: 1-866-724-9394.

"Our motive for this is not financially driven," said Genentech product communications manager Krysta D. Pellegrino. "We do not believe this decision will increase sales of Lucentis. We expect doctors will still have access to Avastin."

Following the AAO meeting, Genentech cooperated in the compromise that allows sales of Avastin directly to eye care physicians who can specify delivery to compounding pharmacies for appropriate formulation needed for treating age-related macular degeneration.

Does Avastin Work As Well As Lucentis In Treating Macular Degeneration?

Besides cost issues, another area of concern involves which drug works best for treating macular degeneration. Because no large studies have been completed, the question remains unanswered.

"Tens of thousands of doses of Avastin were given nationwide, while doctors were waiting for ranibizumab [Lucentis] to get approved," University of Iowa Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator Edwin M. Stone, MD, PhD, wrote in an editorial published in the October 2006 issue of the New England Journal of Medicine. "And it often worked very well. But what no one knows at the moment is whether one drug is really significantly better than the other."

The editorial noted that Lucentis costs more than $2,000 per treatment, while Avastin costs less than $150 per treatment. This price discrepancy could be highly significant for people who have limited or no health insurance coverage.

The New England Journal of Medicine article points out that Medicare covers Lucentis injections under Part B of the plan, but that the 20 percent co-payment required for each monthly injection still represents a significant expense. Supplemental insurance might be available to defray at least some costs involved with co-payments.

Medicare as of early 2010 provides a $50 reimbursement per injection when Avastin is used for macular degeneration treatments. In late 2009, eye doctors successfully lobbied to overturn a new Medicare directive that reduced reimbursements for Avastin from $50 to $7 per injection. Medicare's action temporarily forced eye doctors to use Lucentis instead of Avastin.

But if you do the math, Avastin still might be the cheaper alternative even for people covered by Medicare or health insurance when a 20 percent co-payment equals about $400 per treatment for Lucentis, versus $150 per treatment for Avastin.

Again, supplemental insurance may be able to reduce out-of-pocket expenses associated with Lucentis treatments.

In May 2007, British researchers published a cost analysis comparing the two treatments in the British Journal of Ophthalmology. Researchers concluded that Lucentis, which is about 50 times more expensive than Avastin, would need to be 2.5 times more effective to justify the additional cost. Researchers indicated that Lucentis, compared with Avastin, does not appear to be as cost-effective.

SEE RELATED: Idiopathic Juxtafoveal Telangiectasia (Macular Telangiectasia)

More About Lucentis And Avastin

Both Lucentis and Avastin are produced by the same company — Genentech, based in San Francisco. But there are differences between the two drugs.

Lucentis is administered in the form of smaller molecules, which is thought to give Lucentis an advantage over Avastin in its ability to penetrate the eye's retina and halt abnormal blood vessel growth contributing to advanced macular degeneration and scarring that causes blindness.

Genentech company officials have repeatedly told news reporters that considerable expense was involved in developing Lucentis as a macular degeneration treatment and in funding clinical trials proving the drug's safety and effectiveness.

Genentech officials have said they have no intention of also funding clinical trials for Avastin as a treatment for macular degeneration, now that Lucentis has FDA approval and the need for an effective macular degeneration treatment has been met.

Instead, U.S. government funds are being used to compare effectiveness and safety of the two different treatments. In early 2008, plans were announced for enrollment of participants in the two-year Comparison of Age-Related Macular Degeneration Treatments Trials (CATT), sponsored by the National Eye Institute at 43 study sites.

Where The Lucentis-Avastin Debate Now Stands

In the past, serious safety concerns were expressed about off-label use of Avastin as a macular degeneration treatment. This is partly because the FDA in January 2005 warned that Avastin, when used to treat colon and other cancers, significantly increases the risk of stroke, heart attack and other related adverse health events.

However, the British Journal of Ophthalmology in July 2006 reported results of one Internet survey among eye doctors who reported no adverse health side effects related to use of Avastin for macular degeneration, seemingly because relatively low doses of the drug are injected into the eye.

But other researchers commenting in the journal point out that long-term safety risks of Avastin remain unknown. For treatment of cancer, higher doses of Avastin are administered through an intravenous (IV) infusion into a blood vein, such as in the arm.

"Currently, there appears to be a global consensus that the treatment strategy using intravitreal [eye injections of] Avastin is logical, the potential risks to our patients are minimal and the cost-effectiveness is so obvious that the treatment should not be withheld," Philip J. Rosenfeld, MD, PhD, of Miami's Bascom Palmer Eye Institute wrote in an editorial published in the July 2006 issue of American Journal of Ophthalmology.

In a commentary published in the October 2006 issue of the British Journal of Ophthalmology, British researchers from Liverpool noted that Lucentis was developed for macular degeneration treatment because of concerns that Avastin would be unable to penetrate the eye's retina effectively.

The British writers noted that Genentech officials followed correct protocol and undertook the expense and research involved with making sure an effective treatment, Lucentis, was fully tested specifically as a treatment for macular degeneration.

The British commentary weighed both sides of the issue: "Is it fair that Genentech should lose out? What of the patients (or countries) who cannot afford Lucentis? Is it fair that treatment is available to only those who are wealthy?"

These questions underscore the complexities of the controversy.

Medical researchers involved in the debate have proposed that more investigations be made into whether fewer dosages involving both Lucentis and Avastin might achieve the same positive results, thus helping reduce treatment costs. Investigations also are exploring effectiveness of combining Lucentis with other therapies to reduce frequency of dosages.

In one small study reported in 2008, Munich investigators found that Lucentis was slightly better than Avastin when used as an additional treatment for people with advanced AMD and who needed more eye injections after receiving Avastin treatments initially.

Also, in what might be an isolated incident, Genentech reported in late 2008 that off-label use of Avastin caused an outbreak of serious eye inflammation at four Canadian centers where people received eye injections for macular degeneration.

The way Avastin is formulated also could be associated with certain cases of high eye pressure after injections, one presenter said at a 2009 AAO conference.

One small study reported in October 2009 found no difference in effectiveness between Avastin and Lucentis, according to investigators at the Boston University School of Medicine (BUSM) and the VA Boston Healthcare System.

In a follow-up report announced in October 2010, the same researchers noted no significant differences in one-year outcomes between the Lucentis and Avastin groups studied.

However, researchers say that cost differences for those receiving treatment are major at about $40 per injection for Avastin and $2,000 per injection for Lucentis.

The Lucentis-Avastin debate may be settled when the two-year NEI clinical trials comparing the two treatments are completed. Enrollment in the CATT study ended in early 2010, and first-year results were reported in May 2011.** The preliminary conclusion is that the two drugs are about equal in their effectiveness, but safety measurements and long-term effects will be studied further during the second year of CATT.

[Read more about other FDA-approved macular degeneration treatments, as well as investigational treatments.]

*American Journal of Ophthalmology. March 2005. **Ranibizumab and bevacizumab for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. New England Journal of Medicine. Online May 2011.

Page published on Wednesday, February 27, 2019