Acanthamoeba keratitis: What contact lens wearers need to know

Acanthamoeba eye infections in contact lens wearers are rare but serious — for example, a Denver woman lost sight in one eye after contracting the amoeba while swimming — and these infections often start because of improper lens handling and poor hygiene. If you have eye pain, eye redness that won’t clear up with drops, blurry vision, light sensitivity, excessive tearing or feel as if there is something in your eye, you should see your eye doctor.

If untreated, Acanthamoeba keratitis will lead to severe pain and possible vision loss or blindness. In the case of the Denver woman, Stacey Peoples needed a corneal transplant. She now has normal vision with glasses, according to a Today story.

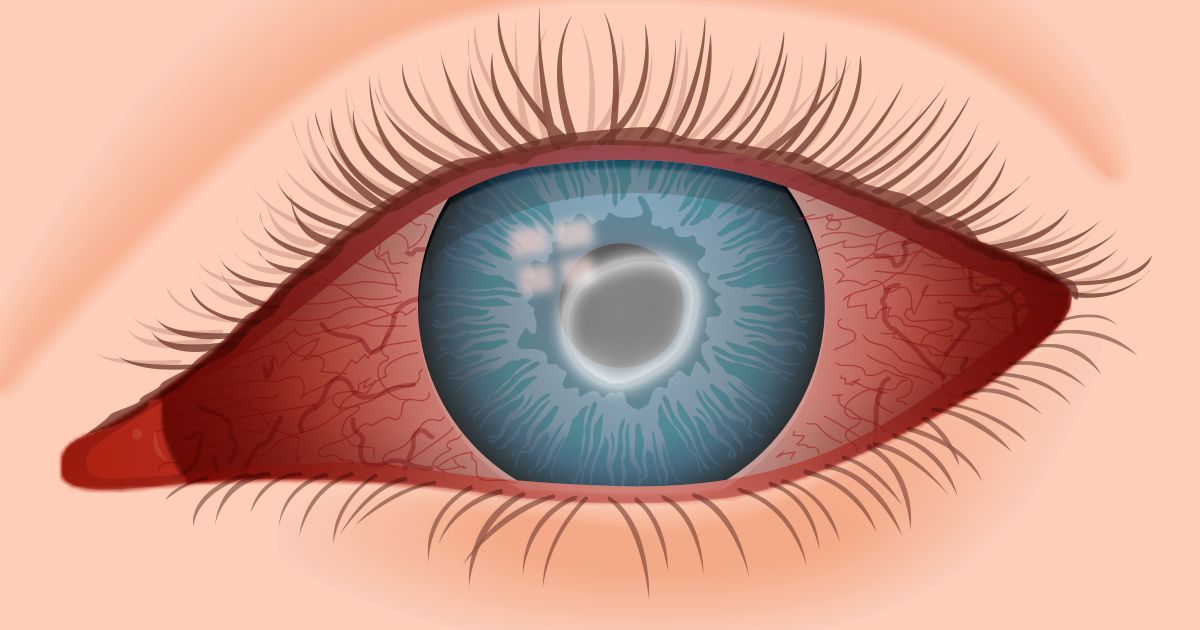

Advanced Acanthamoeba keratitis can cause a white “ring” to cover the iris, as well as redness in the white of the eye. (Also read about conjunctivitis, another cause of eye redness.)

To avoid Acanthamoeba keratitis and all contact lens-related eye infections, be sure to carefully follow the lens care, handling and wearing instructions you receive from your eye doctor.

What is Acanthamoeba keratitis?

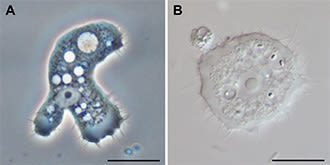

Acanthamoeba are naturally occurring amoeba (tiny, one-celled animals) commonly found in water sources, such as tap water, well water, swimming pools, hot tubs, and soil and sewage systems.

If these tiny parasites infect the eye, Acanthamoeba keratitis results.

First diagnosed in 1973, an estimated 85% of U.S. Acanthamoeba keratitis cases affect contact lens users, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). In the developed world, the incidence of Acanthamoeba keratitis is approximately one to 33 cases per million contact lens wearers.

That incidence may be increasing, though.

UK researchers at University College London found that rates of Acanthamoeba keratitis have nearly tripled since 2011 in the southeast of England. Moorfields Eye Hospital, where cases across the southeast of England are treated, recorded an average of 50.3 cases of Acanthamoeba keratitis.

Acanthamoeba outbreaks among contact lens wearers

In recent years, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and other researchers have noted sporadic outbreaks of Acanthamoeba keratitis cases among contact lens wearers.

In 2007, for example, the CDC released several public health warnings regarding Acanthamoeba keratitis associated with use of the contact lens solution Complete MoisturePlus, manufactured by Abbott Medical Optics (AMO) — formerly Advanced Medical Optics.

The CDC said a sevenfold increase in the risk of developing Acanthamoeba keratitis associated with use of the contact lens solution prompted AMO to withdraw Complete MoisturePlus from the market. The contact lens solution itself was not contaminated, but it seemed to be ineffective in preventing Acanthamoeba keratitis.

The CDC has issued similar warnings concerning fungal eye infections associated with the use of Bausch + Lomb’s ReNu With MoistureLoc contact lens solution, which was removed from worldwide markets in May 2006.

In 2011, the CDC and state and local health officials investigated unusual clusters of Acanthamoeba keratitis cases to find common risk factors to reduce future infections. The preliminary analysis found contact lens hygiene practices played a role but did not result in a call to stop the sales of any contact lens-related products.

What causes Acanthamoeba keratitis?

Factors and activities that increase the risk of contracting Acanthamoeba keratitis include using contaminated tap or well water on contact lenses, using homemade solutions to store and clean contacts, wearing contact lenses in a hot tub and swimming or showering while wearing lenses.

Acanthamoeba is a single-cell organism that exists in nature in two forms: an active, growing form (left) and a dormant, stress resistant cyst (right). (Images: Morales, Khan and Walochnik [CC BY 2.0], via Wikimedia Commons)

A dirty lens case also can be a source of Acanthamoeba infection.

In addition, some scientists theorize that new U.S. Environmental Protection Agency regulations aimed at reducing carcinogenic (potentially cancer-causing) products such as disinfectants in the water supply may have inadvertently boosted microbial risks, including an increased likelihood of finding Acanthamoeba in water supplies.

Other researchers associate recent increases in contact lens-related eye infections with the introduction of “no-rub” lens care systems that may result in less effective contact lens cleaning and disinfection.

But regardless of the cause of the increase, Acanthamoeba can be killed easily, especially when rubbed off the lens surface during cleaning. In the end, good contact lens hygiene is the best way to prevent Acanthamoeba keratitis.

SEE RELATED: Eye worms

How do you know if you have Acanthamoeba keratitis?

Symptoms of Acanthamoeba keratitis include red eyes and eye pain after removing your contact lenses, as well as tearing, light sensitivity, blurred vision and a feeling that something is in your eye.

With these types of symptoms, you should always contact your eye doctor. But keep in mind that Acanthamoeba keratitis is often difficult for your eye doctor to diagnose at first, because its symptoms are similar to pink eye symptoms and those of other eye infections.

Diagnosis of keratitis often occurs once it is determined that the condition is resistant to antibiotics used to manage other infections. A “ring-like” ulceration of your corneal tissue may also occur.

Unfortunately, if not promptly treated, Acanthamoeba keratitis can cause permanent vision loss or require a corneal transplant to recover lost vision.

How you can reduce the risk of getting Acanthamoeba keratitis

There are several easy ways to greatly reduce the chance of getting this sight-threatening condition — and, in fact, any type of contact lens-related eye infection:

Follow your eye doctor’s recommendations regarding care of your contact lenses. Use only products that he or she recommends.

Never use tap water with your contact lenses. The FDA has recommended that contact lenses should not be exposed to water of any kind.

Do not swim, shower or use a hot tub while wearing contacts. If you do decide to wear your lenses while swimming, wear airtight swim goggles over them. (Read about additional strategies for swimming with contact lenses.)

Soak your lenses in fresh disinfecting solution every night. Don’t use a wetting solution or saline solution that isn’t intended for disinfection.

Always wash your hands before handling your lenses.

Always clean your contacts immediately upon removal (unless you are wearing disposable contact lenses that are replaced daily). To clean your lenses, rub the lenses under a stream of multipurpose solution – even if using a “no-rub” solution – and store them in a clean case filled with fresh (not “topped off”) multipurpose or disinfecting solution.

Take care of your contact lens case

Cleanliness and proper care are equally important for contact lens cases.

It’s important to clean, rinse and air-dry your contact lens case immediately after removing your lenses from the case. Discard the old solution and rub the inside wells of the case with clean fingers for at least five seconds. Then fill the case with multipurpose solution or sterile saline (not tap or bottled water), dump this out, and store the case upside down with the caps off.

As an extra precaution, you might want to consider sterilizing your empty contact lens case once a week by submerging it in boiling water for a few minutes.

Many eye doctors also say you should discard and replace your contact lens case monthly or, at a minimum, every three months to help prevent contamination.

Prevention is your best defense against Acanthamoeba keratitis. Always use good hygiene during contact lens use and care. And if you notice any unusual eye symptoms that might indicate an infection, immediately consult your eye doctor.

READ NEXT: Neurotrophic keratitis

Parasites — Acanthamoeba — Granulomatous Amebic Encephalitis (GAE); Keratitis. U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. December 2021.

Basics of Parasitic/Amebic Keratitis: Acanthamoeba Keratitis (AK). U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. November 2022.

Acanthamoeba keratitis: a review of biology, pathophysiology and epidemiology. Ophthalmic and Physiological Optics. October 2020.

The epidemiology and clinical features of Acanthamoeba disease in the United States, 1956–2018. Open Forum Infectious Diseases. December 2020.

Page published on Wednesday, January 30, 2019