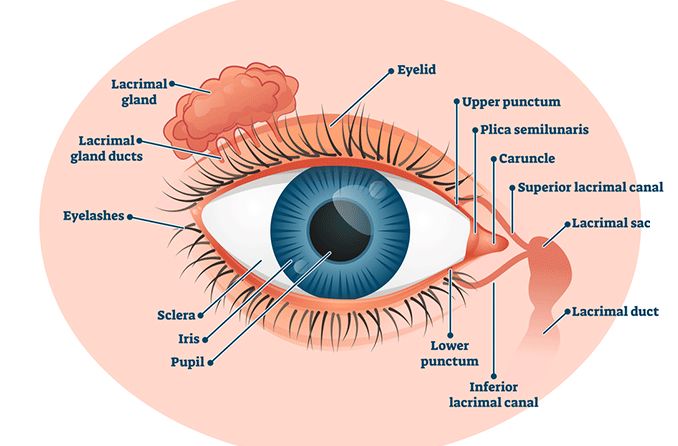

Lacrimal gland

The lacrimal gland

Located above each of your eyes is a lacrimal gland, also called a tear gland, that secretes a lubricating film onto the surface of the eye to keep it cleaned and nourished.

Lacrimal glands drain through the tear ducts, and because they secrete fluids directly onto the surface of the eye (and not into the bloodstream), they are considered exocrine glands.

Anatomy of the lacrimal gland

Each lacrimal gland is shaped like an almond and is located above the outer corner of the eye. The lacrimal artery brings the blood supply, and nerve fibers as well as muscle cells help activate the gland and expel fluid. The nerve fibers can be stimulated by neurotransmitters in the body, and can lead the glands to secrete proteins that protect the eye.

Each lacrimal gland is made up of two parts:

The smaller palpebral lobe

The larger orbital lobe

Although the size of a normal lacrimal gland can vary from individual to individual, the glands are usually symmetrical and similar in size. The lacrimal gland is approximately 2 centimeters (a little under an inch) long.

READ MORE: Punctum of the eye

Tears and tear film

The tear film produced by your lacrimal glands consists of a clear fluid that keeps the surface of the eye moist and prevents it from drying out.

Types of tears

When you feel strong emotions, or your eyes become dry or irritated, your lacrimal glands produce extra tear film, or tears, to try to address the issue. There are three types of tears:

Basal tears – Always present to keep the eyes moist and protected and to help you see clearly.

Reflex tears – Produced to help clear the eyes in reaction to an irritant, such as wind, debris, smoke or fumes.

Emotional tears – Occur when you have an extreme emotional response to something, whether it’s sadness, joy or even anger.

SEE RELATED: Epiphora: Excessive Eye Watering

Tears have 3 layers

Image Source: National Institutes of Health (NIH)

On average, you produce around 15 to 30 gallons of tears a year, and each of those tears consists of three layers:

An outer lipid layer produced by the meibomian glands (more on these below) to prevent the tear film from evaporating.

A middle aqueous layer produced by the lacrimal glands that helps hydrate the eye, repel bacteria, protect the cornea and bring important electrolytes to the surface of the eye. This watery layer also helps smooth the surface of the eye and allows it to refract light so you can see clearly.

An inner mucin layer that helps the tear film spread evenly across the surface of the eye. This layer is produced by conjunctival goblet cells, specialized epithelial cells that secrete mucus onto the surface of the eyes.

SEE RELATED: Blocked tear ducts and blocked tear ducts in babies

Lacrimal gland function

Tear film contains immune system antibodies, enzymes, and antifungal and antibacterial agents that fight germs and protect the eyes from invading pathogens. These antibacterial molecules allow the lacrimal gland to kill many kinds of organisms on the surface of the eye and react to irritants such as pollution and pollen.

Lacrimal glands also secrete growth factors to keep the corneas healthy, able to self-repair if injured, and able to receive oxygen from the air.

Overall, the lacrimal glands secrete a complex fluid rich in antibodies, antimicrobial agents, lubricating fluid, and growth factors that:

Protects the corneas from infection and drying out.

Helps keep the surface of the eye transparent for clearer vision.

Promotes wound healing with special growth factors.

Lacrimal glands vs. meibomian glands

While you only have two lacrimal glands — one over each eye — you have 25 to 40 meibomian glands in your upper eyelid and 20 to 30 in your lower eyelid.

Meibomian glands produce the oils that sit above the eyes’ watery tear film (produced by the lacrimal glands), preventing it from evaporating too quickly. These oils also sit along the edges of the eyelids, forming a barrier to keep your tears in your eyes.

Lacrimal glands, meibomian glands and dry eye syndrome

Dry eye syndrome is a common condition that can cause you to experience feelings of eye dryness, burning, itching and soreness. Dry eye can occur if the composition of your tear film is defective or if any part of the tear production system stops working properly. For example:

As you age, your lacrimal glands begin to secrete fewer tears, which may cause your eyes to feel uncomfortable and dry.

If your meibomian glands are blocked or aren’t secreting enough oil, tears may be quick to evaporate and make your eyes feel dry and irritated. This is called meibomian gland dysfunction (MGD).

Risk factors for dry eye syndrome include:

Advanced age

Computer use

Female sex

Contact lens use

Environmental factors

Health conditions

Certain medications

There are many treatments for dry eye, ranging from eye drops that replace the tear film to antibiotics, anti-inflammatory medications and other treatments like punctal plugs.

Vitamin A and the lacrimal gland

Retinol, a vitamin A derivative, is secreted by the lacrimal gland and is important for the flow rate of tears and for the health of the eyes. Vitamin A deficiency has been linked to the development of corneal ulcers and an increased risk of eye infection.

When to see a doctor

If you notice any new feelings of dryness in your eyes or any drastic difference in your ability to see clearly, schedule an appointment with an eye doctor.

READ NEXT: Dacryocystitis: Causes, symptoms and treatments

The lacrimal gland. TeachMeAnatomy. September 2018.

Tear duct. American Academy of Ophthalmology. February 2018.

Lacrimal gland masses. American Journal of Roentgenology. September 2013.

Facts about tears. American Academy of Ophthalmology. December 2016.

The immune response of the lacrimal gland to antigenic exposure. Current Eye Research. July 1987.

What is the anatomy of tear film relevant to dry eye disease (keratoconjunctivitis sicca)? Medscape. December 2019.

Tear system. Cleveland Clinic. Accessed April 2021.

Review: The lacrimal gland and its role in dry eye. Journal of Ophthalmology. March 2016.

Page published on Wednesday, April 21, 2021