At long last, a typeface designed specifically for low vision readers

Modern medicine has turned low vision into a public health paradox: While blindness is declining worldwide, more people are growing old enough to lose their vision.

Therefore, an aging population poses a mounting low-vision challenge — especially when it comes to reading text set in type. Typefaces define the shape of text, making it legible enough for most readers while creating difficulties for people whose low vision can’t be corrected.

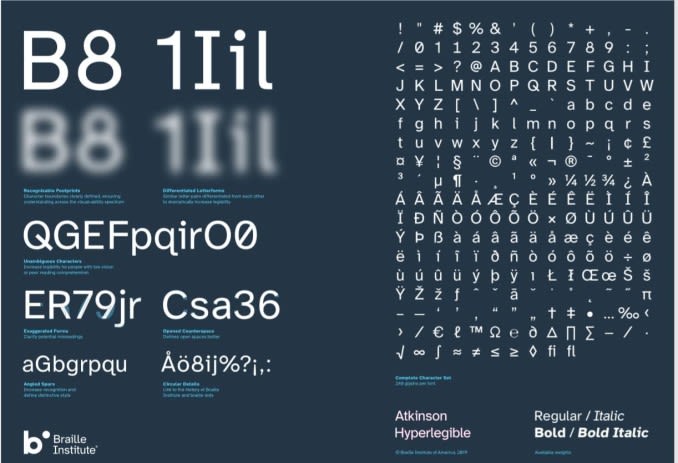

That could change with the arrival of a new typeface developed jointly by the Braille Institute in Los Angeles and Applied Design Works in New York City. The typeface, called Atkinson Hyperlegible, is named for J. Robert Atkinson, who founded the Braille Institute in 1919. The Braille Institute hired Applied to update its branding for the 21st century as part of its centennial celebration.

Blinded in a gunshot accident, Atkinson pioneered publications and technologies to help sightless people read in braille. In the space of a century, however, the institute’s typical clientele has shifted dramatically.

Low-vision readers and braille

“People may be surprised that the vast majority of the students who come to Braille Institute have some degree of vision,” says Sandy Shin, the institute’s vice president for marketing and communications. “They're not 100% blind.”

Thus, most of the Braille Institute’s 37,000 clients across Southern California don’t depend on the dot-based braille language. Instead, they rely on spoken-word tools and accessibility standards that encourage text publishers to think more carefully about the legibility of words on pages.

Those standards help developers build apps and websites that let low-vision users customize their type size, color, background, spacing and other variables, all crucial to readability on smartphones, tablets and computer screens. While these tools make a big difference with digital materials, magnification is usually the only adjustment option available for text on printed materials like books, fliers and pamphlets.

That leaves even more to think about, especially in the specific shapes that are central to typography. “The shape of the letters is a major component in reading,” says Elliott Scott, a creative director at Applied Design Works and lead designer of Atkinson Hyperlegible. “You want to increase everybody's chances of reading well — and comprehending what they're reading.”

LEARN ABOUT NEW TECH IN LOW VISION: Find an eye doctor near you.

Typeface types, past and present

Typography is as old as the printed word. The typographer carefully designs every arc and segment within each letter, numeral and special character in a written language. For instance, the amount of white space in the letter “o” and the arcs of the letter “m” conform to the typographer’s vision for a typeface. Every typeface is designed for visual consistency and aesthetic appeal.

Typefaces typically fall into two categories — serif faces, which have curved accents at the tips of each character, and sans serif faces, which lack these accents (sans means “without” in French).

Examples:

Times New Roman is a traditional serif face.

Arial is a modern sans serif face.

These and thousands of other typefaces work fine for most readers — but not so much for people with low vision.

Contrast how “Braille Institute” looks in each face:

Braille Institute (Times New Roman)

Braille Institute (Arial)

Here’s the same type in Atkinson Hyperlegible:

Note the differences: The lower-case “i” has a small tab on the top left, while the lower-case “l” and “t” have a small base curving to the lower right. These visual flourishes are more like serifs in a typeface that’s otherwise designed to look like a sans serif face.

“Typefaces that have more character are generally easier to read,” says Craig Dobie, founding creative director at Applied Design Works. Traditional serif faces like Times New Roman have some of that character, but the Braille Institute needed a more contemporary typeface like Helvetica, Dobie says, because the organization is modernizing for the 21st century.

The challenge for modern, sans serif faces is that they accept a certain level of ambiguity. For example: When “Illness” is capitalized in Helvetica, the first three letters look identical. Atkinson Hyperlegible’s small, serif-like flourishes remove these ambiguities.

“It does some things a modernist font doesn't usually do, so it's breaking the rules a little bit,” Dobie says. “But it's breaking the rules for the right reason — to increase legibility.”

How to create a new typeface

Applied Design Works faced a unique quandary when it started its rebranding project for the Braille Institute: “We really felt like we weren’t going to be doing our job properly if we couldn't find a typeface that was highly legible,” Dobie says. “And we couldn't.”

To create Atkinson Hyperlegible, Scott and his colleagues at Applied had to painstakingly craft hundreds of shapes — letters, numerals, punctuation marks and symbols — to ensure that a low-vision reader could distinguish between each character. For example, a zero had to look different from an uppercase “O” and spacing within a lower-case “c” had to look different from a lower-case “b.”

“Creating a typeface is not an easy thing to do,” Dobie says. In addition to creating the characters, the agency submitted versions to the Braille Institute to get feedback from some of their low-vision clients. That feedback, plus an in-depth study of legibility research, helped the agency develop a more effective typeface.

A typeface for low-vision readers

The creation of Atkinson Hyperlegible isn’t just to help one nonprofit serve its low-vision community. It’s about bringing accessibility to the wider world.

“In the general public's awareness, that idea of accessibility is gaining a lot more traction, and we, as graphic designers, see a lot of articles on that subject,” Dobie says. “I think that it'll increase the pressure on organizations to be more inclusive.”

Atkinson Hyperlegible is already making waves, winning Fast Company magazine’s 2019 Innovation by Design Awards for Graphic Design.

And that’s just the start. The Braille Institute plans to publish the typeface on its website in early 2020, making it available for anybody to download onto their devices. The institute also plans to collect data on the typeface’s effectiveness, hoping to use that data to persuade tech giants like Microsoft, Apple and Google to include Atkinson Hyperlegible on their platforms.

Thus, what started as a local branding effort may one day help low-vision people in Southern California — and perhaps around the globe. As Sandy Shin of the Braille Institute puts it: “This can make a really significant difference in their day-to-day lives.”

READ NEXT: How to make the internet easier to navigate with impaired vision

Page published on Friday, November 8, 2019